Making Notes from Reading

Guidance on taking effective notes rather than getting swamped in them.

Why take notes when we read?

When it comes to recording key information we wish to refer to later, we can photocopy physical texts, and copy and paste from digital ones. Why, then do we need to make notes? Well, making notes when we read has several benefits. The most obvious ones are that it helps us:

- Actively engage with the material, so we begin to process the information we’re reading

- Develop our knowledge and understanding of a topic

- Identify the most important and relevant points so that we can distinguish the need to from the nice to know (and thus avoid trying to learn *everything*)

- Remember key points so that we can use our notes later down the line when we’re writing essays or as revision aides etc.

However, university study – whatever the subject or level – is not just about learning and remembering information. Not recognising this can lead to you becoming the human photocopier. You may end up with swathes of information you might not need and your notes could well end up being too dense and overwhelming to be useful. Additionally, if you just end up unselectively copying out reams of facts and information you are, potentially, stifling your critical and creative thinking. This could lead to you producing overly descriptive assignments.

As well as increasing your knowledge of a topic, your reading also needs to help you develop your own thinking and ideas so that you can tackle assignment questions and tasks without merely repeating information you have read elsewhere. At university, the expectation is that you will use the material you draw from your reading to:

- Back up your points or support any statements you make

- Answer the questions and address the problems you are set

- Suggest recommendation and solutions, illustrate with examples

Strategic note-taking: what do you need to take notes of?

The first thing you need to note when reading is the full bibliographic details, including the page numbers of any direct quotations you might copy or location of any specific information you might want to cite. This will help you find the original information again if you want to go back to the text and check it, and also ensure that you have everything you need for your assignment’s bibliography. You also need a very clear system for indicating which notes are verbatim copies, which are your own paraphrases, and which are your own thoughts.

Identifying your purpose and considering what you will use information for will help you become more selective when taking notes. If you clarify your key questions, aims and needs, you have a clearer idea of what you might need to note down. It’s like deciding what to cook for dinner, then shopping for the specific ingredients. You might also find it helpful to think about how you might use the notes later on, which will help you decide how much detail to record and in what form. If you think you might use something as a full quotation in your assignment, you will need to copy the whole thing; if you think you will just paraphrase or cite it, then a summary in your own words, in shorthand even, will be enough.

When you are reading, you are not just noting down what the text says, but your own rections to it. If you are looking to develop a critical stance on a text, you may wish to note down your own thoughts, reactions and any links to other relevant things you’ve read. You may also be noting down what use you anticipate for these notes, as well as follow-up questions to pursue in later reading.

Note-taking strategies

There are various approaches to note-making, such as linear bullet points or more visual non-linear mindmaps, but there are two which are particularly relevant for reading.

SQ3R (or SQRRR)

SQ3R stands for: survey, question, read, retrieve, review and involves the following steps:

- Survey: skim the text to get an outline/overview and develop a sense of which parts or sections might be useful. Note any headings and subheadings, along with things like figures, tables and summaries.

- Question: now that you have a sense of what content the text covers, what questions do you have to help lead you to do a deeper understanding? Your question could be “what does that particular term mean?” or “how might I use that information?”

- Read: now you have specific questions in mind, you will be able to read actively in order to find the answers.

- Retrieve: begin processing and understanding the material by recalling the main points as if you were explaining them to someone else. You could do this verbally or in writing

- Review: review the material by repeating the key points back to yourself in your own words.

- Useful for:

- Keeping on track: by prompting you to formulate specific questions you’d like your reading to address, this strategy encourages you to read strategically and actively, and can help you stay focused.

- Processing your learning: putting what you’ve read into your own words is a good way of developing and checking your understanding. This can help you move away from mere recall towards a deeper conceptual understanding.

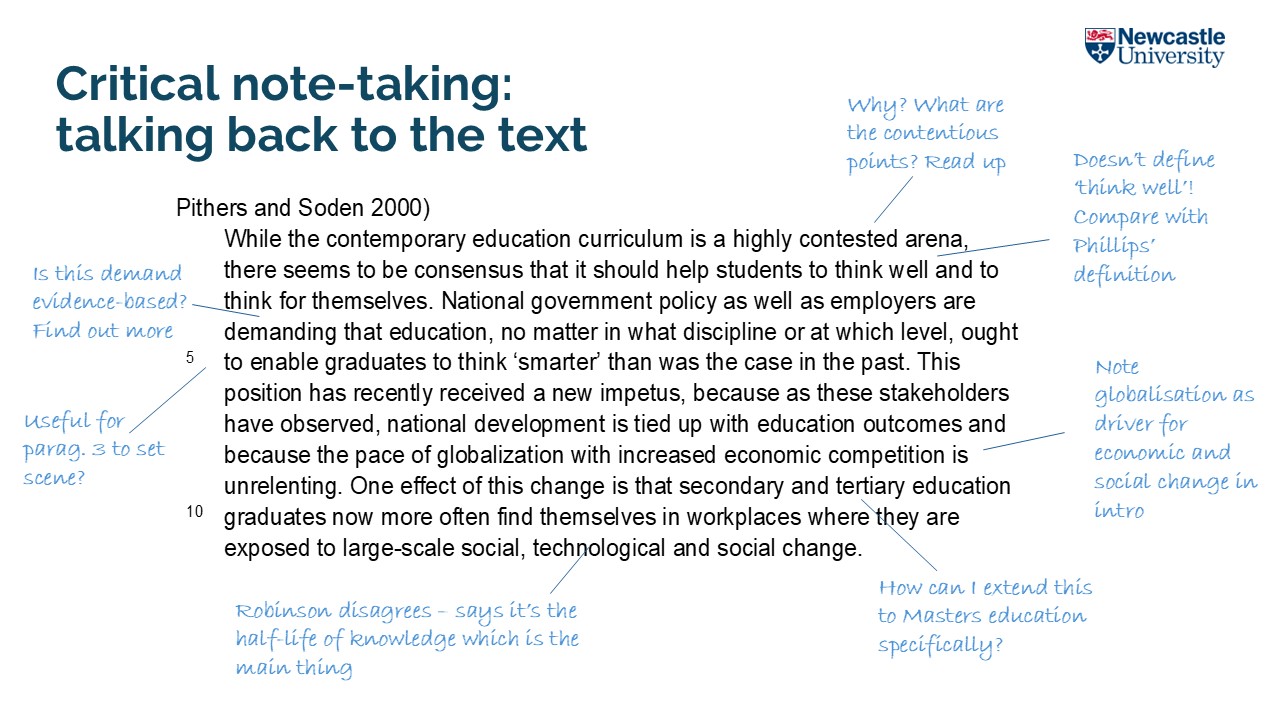

Critical note-taking: talking back to the text

Building an argument of your own means reading not just for information, but for your own response to that information. That means that successful notetaking has an element of critical thinking.

When you’re making notes, try to record not just what the text says, but your own reaction to it.

- Is it relevant for your purpose? How and where might you use it in your own essay?

- What do you think of it? Is the point convincingly argued and well evidenced?

- Do you agree or disagree with it?

- How does it relate to other things you’ve read? Does it support, add to, contradict or show a different perspective to other texts?

- Is there anything you don’t understand or need to know more about?

Critical note-making means talking back to the text, having a dialogue with it. You could annotate it with your own questions and comments in the margin or in your own notes as you go, to record your response to it.

Reflecting on note-taking from your reading

Use these prompts to help you select the most suitable strategy and approach, and to evaluate how well it served your purpose.

Identifying your purpose

- What are you reading for? What specific questions do you have? What are you looking for?

- What do you need to note down?

- How will you use your notes? Do you need to keep them, or are you just looking to make some very rough notes to help prompt your thinking?

Selecting your strategy

- Do you have a ‘tried and tested’ strategy that you feel works well for your purpose?

- If you’re stepping up a level (i.e. from school to university or from Stage 2 to 3), do you think your usual notetaking strategies will still work for you? Why or why not?

- Are you looking to experiment with a new strategy because previous ones haven’t worked so well or because you don’t think your regular strategies would suit this purpose?

- Which strategies have you tried before for different purposes? Do you think you could use them for this one, or not?

- Which new strategies are you most keen to try and why?

- Which new strategies are you reluctant to try and why?

- Of the strategies you’ve narrowed down so far, which would be best for your purpose and why?

Evaluating your strategy

- Overall, how well did that strategy suit your purpose?

- What were the strengths of your chosen strategy? What was it particularly useful for, and what did it allow you to do?

- What were its limitations? What weren’t you able to do?

- Did you find yourself losing focus at times? Did you find yourself getting bored? If so when and why?

- Did you get bogged down in places and slip into copying out information you didn’t necessary need? Or did you remain focused and on track?

- How useful were the notes you produced? Did they fulfil the purpose you’d outlined?

- Were the notes too detailed and dense? Were they too sparse – with key points omitted or not fleshed out enough? Or were you able to capture the exact level of detail you needed?

- When using your notes, were you able to find specific bits (i.e. specific quotations or facts) readily?

- If your chosen strategy didn’t quite suit your purpose this time, are there any other purposes that strategy might be more useful for?

- What other strategies might you try in future?