Note-taking Strategies

An overview of the different approaches to note-making. Experiment to find the best way for you.

Choosing your tools

Once you’ve identified why you’re taking notes and what you need to take notes of, think about what tool would best help you achieve your purpose. You might not use the same tool every time: some are better than others depending on the job you want them to do. As you experiment with different ones, think about their pros and cons: what are they really good for and what are they not so good for?

Paper versus digital

When it comes to tools, you have a decision between paper or digital. Think about your own personal preferences and needs here, as well as how you will store and use your notes. Whatever medium you choose, be wary of perfectionist tendencies. It can be counter-productive to spend ages painstakingly producing a polished set of notes.

Paper may be better if:

- You want to prompt your critical and creative thinking by capturing your initial thoughts about your reading either in very rough prose or by doodling or freewriting

- Avoid the distractions of social media etc. when you are reading or listening to a lecture or video

- You sometimes confuse your own notes with someone else’s words or ideas when copying and pasting between the original and your own document

Consider what size paper would serve you best, lined or unlined, which orientation and whether bound in a note-book or looseleaf

Digital may be better if:

- You feel you need to produce a very neat, ordered set of notes

- You would like to take advantage of software to aid the note-taking process, like the speech to text function, more flexible organisation or searchability

- You want to have easy access to all of your notes on a portable device wherever you choose to study

There are too many note-taking apps available for us to review and recommend them here, but do explore and ask your peers for suggestions.

It may be that you don’t decide to use either one or the other but a blend of the two. For instance, you might find it useful to use digital tools and software to record, store and re-play key facts and possibly points of action. You may then use paper and pens to jot down your thinking about these initial notes and how you may use them in your assignments.

Organising your notes

Whether you prefer to use the format of paper and pencil or digital, or both, the strategies below can be adapted to suit your own style and preferences:

- Colour: the use of colour might be helpful to not only categorise, but also draw your attention to different aspects of your notes if/when you revisit them at a later date.

- Symbols and/or images: the use of symbols or images might be used to represent information, ideas, connections or questions in a different way. Highlighting aspects of your notes in different ways may provide an aid to more easily recalling or locating this information or may provide a way of creatively engaging with the literature you have read.

- Space: leaving space in or around your notes might be useful if you revisit them so you amend information and/or thinking.

Choosing your strategy

The next step is to choose how you will take notes. There are several strategies to explore. As always, think about what would best help you achieve your purpose and what you will be using your notes for. Again, you may switch between different strategies depending on your purpose.

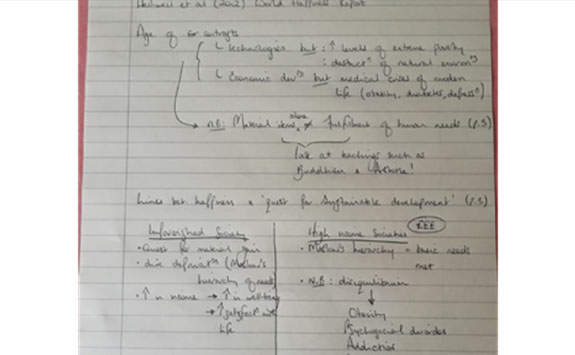

Standard Linear Notes

Linear notes are written in a list-like format down the page and organised according to numbered points or headings and subheadings.

Useful for:

- Analytical tasks: arguments and processes can be broken down into subsections with further definitions and explanations.

- Processing your learning: your memory finds it easier to recall structures, which can then act as a prompt to recall further detail (especially if you use punchy words for key headings or ideas).

- Keeping track: this strategy can help you follow the order of the lecture or text you’re reading so you can see how arguments are built and developed, or note the key points from each section of a paper. This may be useful if you are summarising a text or lecture.

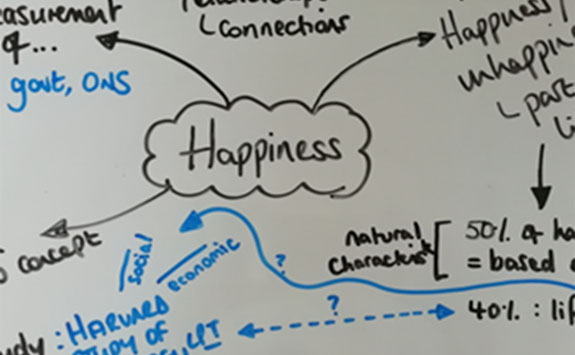

Diagram / non-linear notes

These notes typically start from a main idea to which you can add related information or concepts, using lines to show relationships between them. Turning your page to landscape may help to maximise space although page orientation may depend on the style of notes and/or personal preferences.

There are several versions of these note-taking techniques:

- Mind maps (also called spider diagrams) contain key words or phrases in bubbles at the end of lines or on a line itself which can then lead to further lines or sub-branches.

- Pattern notes look like mind maps, but build in mnemonic (memory) triggers, such as doodles, cartoons and symbols, around key points.

- Nuclear notes combine the structured aspect of linear note-taking with the visual representation of mind maps by connecting several lists to the central idea. Sketchnoting uses a much freer layout more like a graphic novel and greater use of doodles, graphics and hand drawn images and scenes to capture ideas and structures.

- Concept maps appear like a hierarchical family tree, showing ideas branching down from a central idea at the top of the page. The lines between the ideas might have a phrase explaining the connection.

Useful for:

- Getting analytical: this strategy can help you move beyond the original structure towards creating your own order and connections between ideas. Additionally, because of the way these notes are spatially organised, they can help you think through or explain the causal connections between ideas.

- Processing your learning: good for getting an overview of lots of information and how it all links together. Visualising notes and how ideas are connected can act as an aide memoire for what you have learnt. The process of rearranging linear notes into non-linear helps commit the ideas you are dealing with into the long-term memory. Rather than passively rewriting notes, you are reformulating them meaning that you are actively engaging with the information.

SQ3R (or SQRRR)

SQ3R stands for: survey, question, read, retrieve, review. It is a technique for note-making when reading, but could also work well for videoed lectures. It involves the following steps:

- Survey: skim the text (or watch the video) to get an outline/overview and develop a sense of which parts or sections might be useful. Note any headings and subheadings, along with things like figures, tables and summaries.

- Question: now that you have a sense of what content the text covers, what questions do you have to help lead you to do a deeper understanding? Your question could be “what does that particular term mean?” or “how might I use that information?”

- Read: now you have specific questions in mind, you will be able to read (or watch the video) actively in order to find the answers.

- Retrieve: begin processing and understanding the material by recalling the main points as if you were explaining them to someone else. You could do this verbally or in writing

- Review: review the material by repeating the key points back to yourself in your own words.

Useful for:

- Keeping on track: by prompting you to formulate specific questions you’d like your reading to address or to engage with in the lecture, this strategy encourages you to read strategically and actively, and can help you stay focused.

- Processing your learning: putting what you’ve read into your own words is a good way of developing and checking your understanding. This can help you move away from mere recall towards a deeper conceptual understanding.

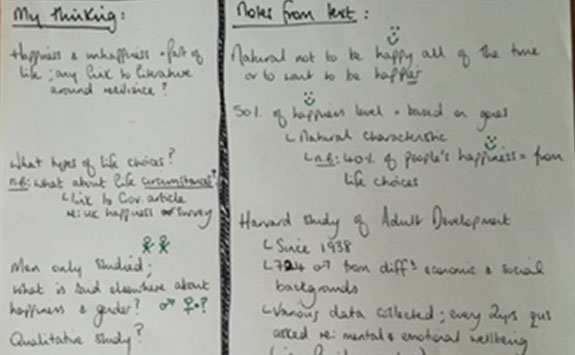

Cornell method / Split page format

This method involves splitting the page into two columns, with the right column roughly twice the width of the left (this can also be done digitally). Detailed notes are written in the right column, and afterwards, key points, reflections, cues or questions can be noted in the left column. Space at the bottom of the page can be used to add a final summary.

Useful for:

- Developing your own thinking: having a response column alongside a column for detail and quotes allows your thoughts and reflections to be clearly separated from the reading or lecture.

- Processing your learning: using paper to cover the right (notetaking) column, you can use the information in the left column as prompts to help you remember the detail or answers to the questions. Or cover both right and left column and use the summary as a prompt to jog your memory.

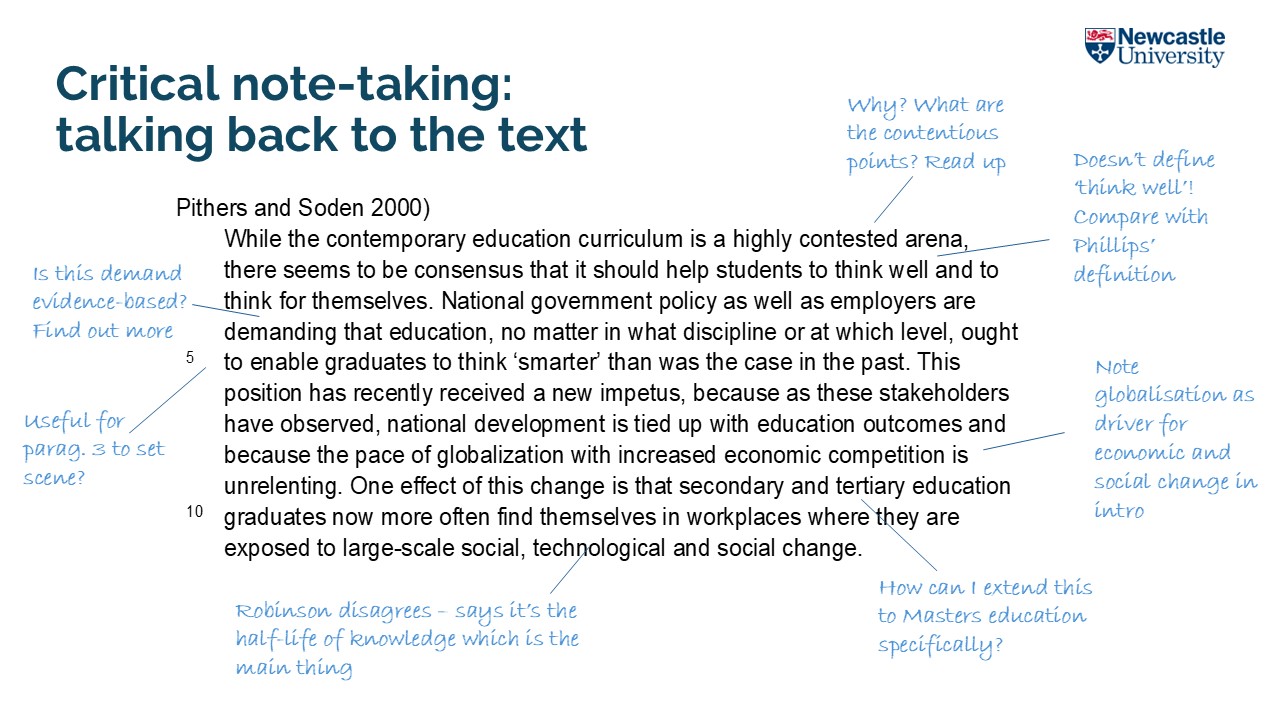

Critical notetaking: talking back to the text

Building an argument of your own means reading not just for information, but for your own response to that information. That means that successful notetaking has an element of critical thinking.

When you’re making notes from reading, try to record not just what the text says, but your own reaction to it.

- Is it relevant for your purpose? How and where might you use it in your own essay?

- What do you think of it? Is the point convincingly argued and well evidenced?

- Do you agree or disagree with it?

- How does it relate to other things you’ve read? Does it support, add to, contradict or show a different perspective to other texts?

- Is there anything you don’t understand or need to know more about?

Critical note-making means talking back to the text, having a dialogue with it. You could annotate it with your own questions and comments in the margin or in your own notes as you go, to record your response to it.

Useful for:

- Getting analytical: this method encourages you to think critically about a text, instead of merely mining it for information

- Processing your learning: talking back to the text encourages you to read actively rather than passively, thus helping you process and apply your learning as well as develop your critical thinking skills.

Other strategies

You may also come across other strategies, which are useful for particular purposes rather than an overall approach:

Matrix Notes This is a tabular notetaking method where columns and rows are organised according to ideas or themes. Information is added in the cells where the rows and columns intersect. This is a handy method of recording different approaches to an issue and encouraging analysis of similarity and difference.

Herringbone Maps These notes are structured like a fish skeleton and are a useful way for noting two sides of an argument. The main idea can be written on the ‘spine’ with different points written on either side on the bones which connect to the spine.

Flowcharts and Timeline Notes These techniques are an effective way to indicate processes or sequence of events.

Reflecting on your chosen approach

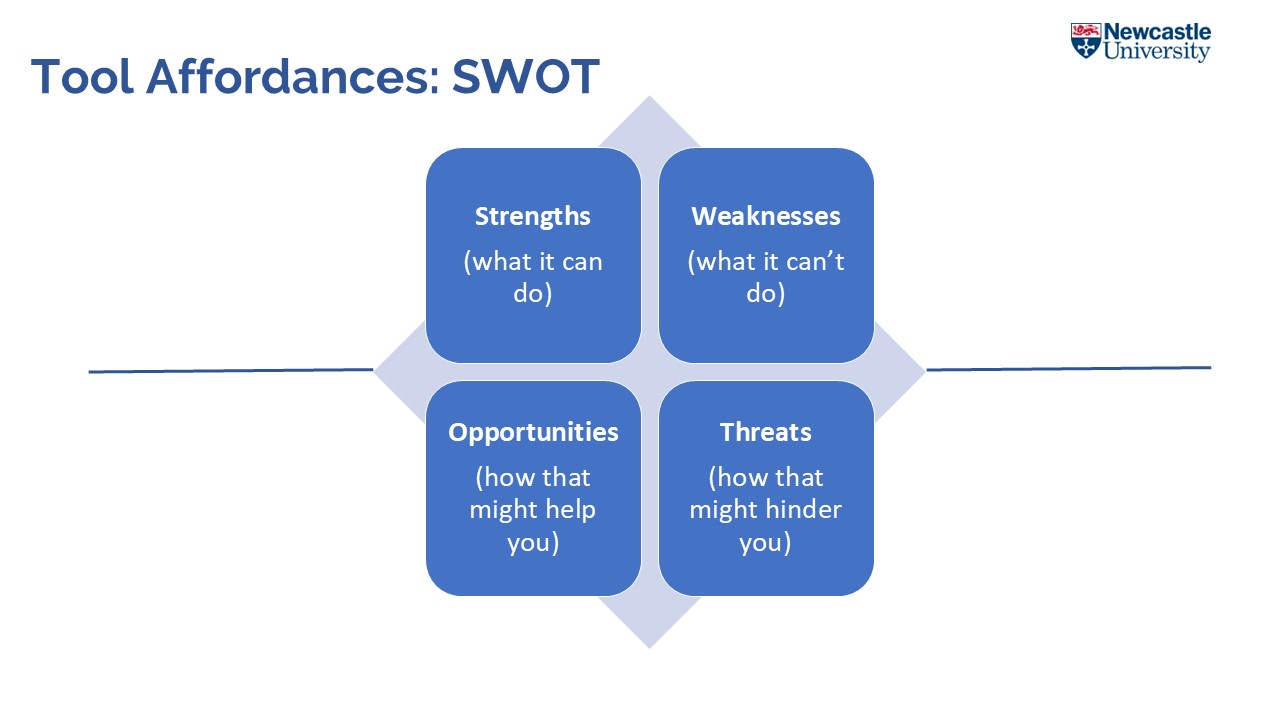

Whichever tool or strategy you use, you could do a SWOT analysis of its “affordances” (what functions it has and what they enable you to do) to see how well it serves your needs:

Whatever format of making and taking notes you use, consider the reasons and purposes for your approach. Is your current approach enabling you to effectively record what you need to help you construct your assignment or revise for exams, for instance? Are there aspects of your current approach which you think could be further developed? Are there other approaches you might like to try?