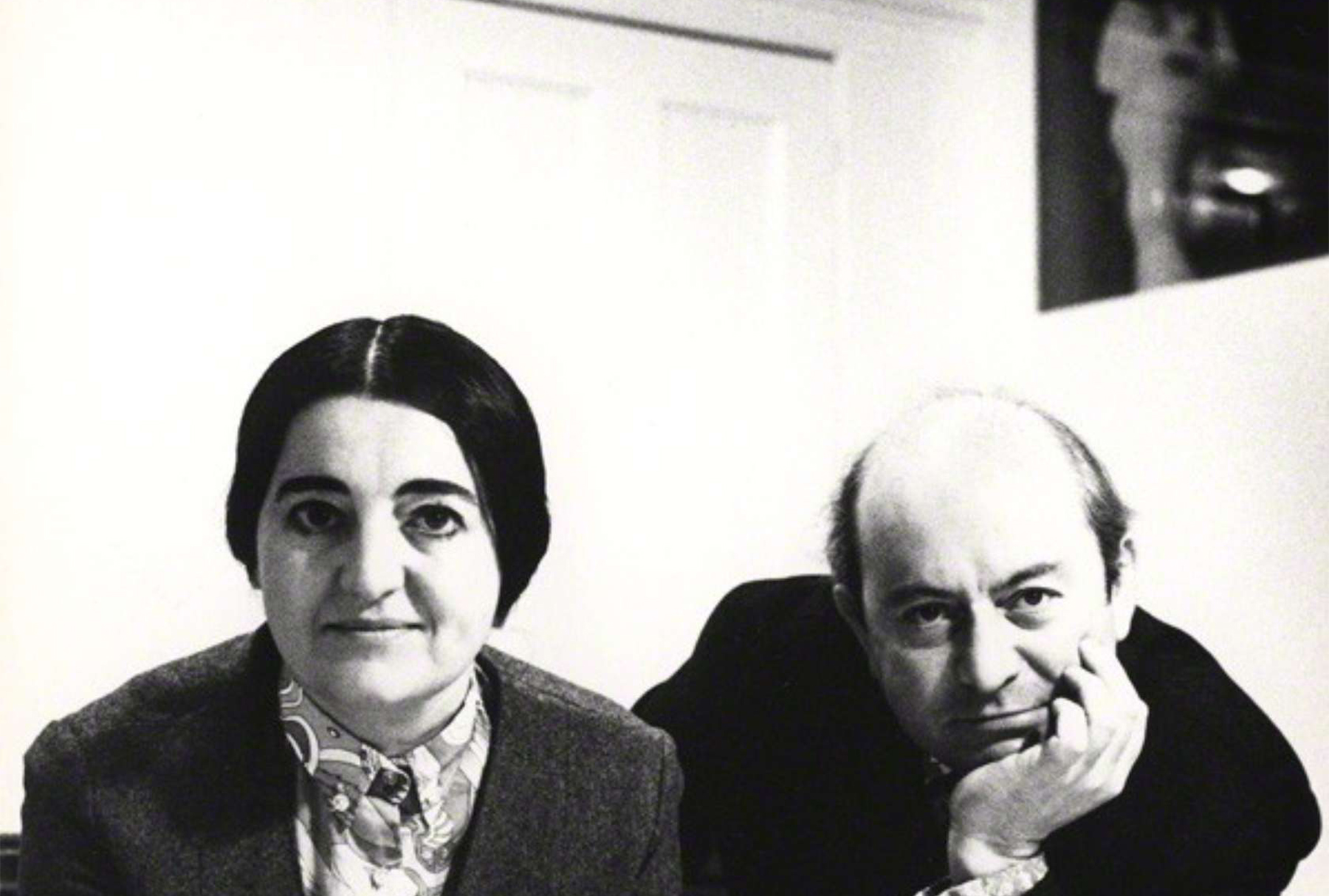

Alison and Peter Smithson

Alison and Peter Smithson (1928-1993 and 1923-2003) were central figures in post-war architecture, included in the single volume histories of the field.

They met at what is now Newcastle University’s School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape, then King’s College, Durham. They married on graduating and maintained a personal and professional partnership for over 40 years. Indeed, they are unique in architecture in that they are spoken about as a single entity.

The couple were thrust to premature architectural stardom in 1950 at the tender ages of just 21 and 26 respectively, when they won the competition to design Hunstanton School. Having worked in the schools' division of London County Council Architects’ Department for less than a year, winning the competition allowed them to set up their own practice.

Architectural historian Reyner Banham called them ‘the bell-wethers [sic] of the young throughout the middle Fifties’. They were certainly at the centre of attention in the world of architecture, being involved with the Independent Group at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London (the so-called ‘fathers of Pop’), as well as spearheading the move to destroy the international modernist group CIAM and establish its replacement, Team 10, in its place.

But perhaps they are most famous for inventing Brutalism, the movement that loves to be loathed and has never been more popular than now. At university, Peter’s nickname was Brutus due to the profile of his head, and the first four letters of this (BRUT), appended by the first four of his partner (ALIS), are just a letter shy of the movement’s name. And they say the Smithsons didn’t have a sense of humour! Although Brutalism turned into something the Smithsons didn’t intend and became synonymous with 1970s concrete construction (‘béton brut’ meaning ‘raw concrete’), it was originally supposed to be concerned with an aesthetic of the everyday and austerity – exposed structure, services, and uncovered materials. It was supposed to be modest and humane. Hunstanton was the movement’s first example, but ideas of the ordinary and everyday continued to motivate the Smithsons’ designs throughout their career.

Their next major building, the Economist Cluster, was their finest and not at all ordinary: completed a decade after Hunstanton, it was a more confident piece of place-making and finely finished. By the time their third major building, Robin Hood Gardens housing estate was completed in 1972, it was already an anachronism. Ideas conceived in 1952 were, by 1972, becoming as unfashionable as the architects themselves and had been more convincingly executed at Park Hill in Sheffield by their students, Ivor Smith and Jack Lynn, a decade earlier.

As commissions thinned out, the Smithsons spent more time teaching and writing. In the 1950s and ‘60s, Peter taught at the Architectural Association and the couple wrote many articles, especially for the magazine Architectural Design, for which they edited several issues such as the Team 10 Primer, and The Heroic Period of Modern Architecture. It is arguably this enduring discursive aspect of their career – their rhetoric and occasionally controversial polemic – which has cemented their place in architectural history and upon which their reputation rests.