The Intersection of Climate Change and Neglected Tropical Diseases

Written by Jelaine Gan & Sheena Davis

10 May 2024

In a wrap

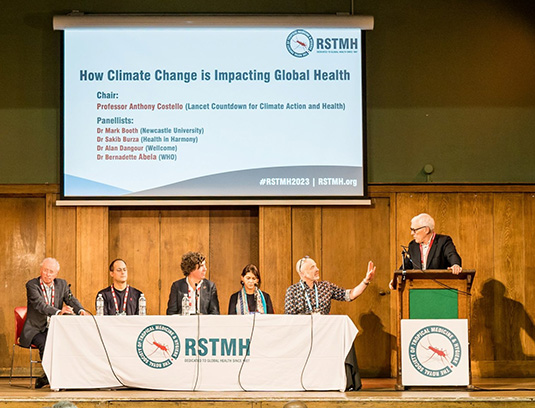

- Dr. Mark Booth's research explores the often-overlooked link between climate change and the transmission of Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs).

- There are significant knowledge gaps regarding the impacts of climate change on the transmission of NTDs and these need to be addressed.

- Securing funding for continued research into the impacts of climate change on NTDs remains a challenge.

When we think of the effects of climate change, often it’s extreme weather events that come to mind. However, we don’t always consider its knock-on consequences on the transmission of diseases.

Dr Mark Booth is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Natural and Environmental Sciences. His research focuses on Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs), a group of over 20 infectious diseases defined as being neglected in terms of investment and interventions. These diseases, such as Dengue and Schistosomiasis, collectively affect billions of people living in tropical and sub-tropical regions each year. Mark specifically looks at how environmental change over space and time affects the transmission of NTDs.

Current collaborations and uncovering knowledge gaps

Mark currently works closely with the NTD unit of the World Health Organisation (WHO). Recently, they have collaborated on a systematic review which identified knowledge gaps surrounding NTD transmission and its relation to climate change. This review revealed a notable scarcity of research on understanding the impacts of climate change on majority of NTDs, with most literature concentrated on diseases transmitted by mosquitoes such as dengue as well as malaria. However, malaria is not considered to be an NTD. Identifying this research gap underscores the urgent need for comprehensive investigations into the relationships between climate change and the transmission of NTDs.

Through his collaboration with WHO, Mark had the chance to connect with other foundations and NGOs that are interested in how climate change may affect NTDs. One such organisation is the End Fund, who are devoted to eliminating and eradicating NTDs. Mark’s work with them has resulted in a white paper which will be presented to policymakers. Recently, Mark was invited to attend COP 28 in Dubai by an UAE-based organisation called Reaching the Last Mile. Mark is also working closely with the All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Malaria and Neglected Tropical Diseases. He advises the group on how climate change may affect transmission of NTDs and is co-ordinating a series of APPG meetings on this topic, starting in June. Through these connections and facilitating conversations around climate change and its impacts on NTDs, Mark is optimistic that more funding will be directed to research addressing the knowledge gaps that were made so apparent by the recent systematic review.

What does the future look like for the transmission of NTDs?

While it is impossible to accurately predict, the mathematical models that have been produced by scientists all suggest that climate change is going to disrupt historically stable patterns of transmission. Extreme weather events such as floods and droughts can alter the suitability of habitats used by host organisms. As Mark explained, “What's evident is the climate crisis is causing such extreme events to be more frequent and that is destabilising these habitats that were historically suitable for transmission. Some habitats are going to become more suitable because they're getting warmer and wetter, the soil is changing and the water's changing. Some habitats are going to become less suitable, and that's going to have the effect of creating fragmentations and less stability in these ecosystems that support these parasites.”

Considering how climate change may influence human migration is also crucial in understanding the future trends in the transmission of NTDs. People are likely to move away from areas where extreme events are becoming increasingly frequent, and in doing so they take parasites with them and possibly lead to the emergence of new infections elsewhere. In fact, the literature suggests that this is already happening, as Mark pointed out, “There was evidence of case reports emerging in different countries where some of these parasites, particularly the helminths which I have concentrated on, have not been so prevalent historically or in fact have been absent, and certainly they did emerge.”

Understanding how climate change could affect future transmissions under different climatic scenarios will be important in planning and mitigating against the potential ramifications on human health and resilience of communities. This will be particularly pertinent in rural tropical areas, where access to healthcare may be limited. By predicting and mapping the effects of climate change under different scenarios, interventions can be better placed to increase the adaptation capacity of communities.

Researcher’s voice

For this section, let’s hear directly from Mark.

What has your journey been to this point? Have there been any major challenge along the way?

"I started my academic career through my first degree in zoology at Imperial College and that's how I became introduced to the world of parasites and parasite epidemiology. It was there that I decided I wanted to start working in tropical areas because they were such an interesting area for me. My PhD was working on helminth infections, and I did a meta-analysis to try and look at co-infections of different parasites to understand why the life cycles of different parasites facilitated co-transmission, particularly gut helminths. I was given the opportunity to take up a welcome-trust fellowship in Switzerland, at the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute. There I worked on schistosomes and malaria, again the through lens of co-infections, and that included field work but also desk space analysis and mapping.

I moved from Switzerland to Cambridge University and worked in a group based in the Department of Pathology, and they were focused on the immunology of schistosome infections. I came in with an idea of combining epidemiology and immunology and using mapping to improve our understanding of the epidemiology and ecology of these infections. I did a lot of work around mapping communities around Lake Victoria in Uganda. This was about environmental change be it through people, place, time and then the immunology was very important to understand some of the underpinning influences as to why certain people, in certain areas at certain times were not responding to treatment. Then I moved to Durham University, where I worked for the Wolfson Research Institute for Health and Well-being. I started to collaborate more with social scientists there, particularly around geography, but also in anthropology. But also, I became more interested in climate change because I was part of a consortium that won an EU framework program 7 grant to look at how climate change may affect transmission of schistosomes and Malaria in East Africa. I did some mapping work, trying to project into the future how temperature might affect the hazards in East Africa in terms of bilharzia. So that was an important project, and it was trumpeted as a success by the EU. We've got a lot of results out of it, it was well regarded, it was very well done. There were lots of publications that came out of it, but it was a one-off call from the EU. That was it and the end of that project coincided with a change in the makeup of the department and the opportunities to find, follow up funding were very limited. Because it was so new and different. So, one of the major challenges really has been to find additional funding to work in that area. So that's been one of the main challenges because these are neglected infections and they don't have the same resources available to them as, say, malaria, TB and HIV. Simply, there isn’t investment available and what investment has been available has largely gone into improving access to medicines rather than academic research."

What are your predictions for your field in the future?

"I think there's going to be more investment into research as our systematic review reveals there has been no research. Yet, we know from the research that has been done that climate change is going to be very disruptive and we need to think of ways of mitigating and adapting. So that's where there's going to be major growth in terms of the opportunities for research, but also implementation and translation into policy.

I have an optimistic outlook now, but it has taken over a decade to get to this point. So, if you'd have interviewed me two years ago or even a year ago it would have been a different story. I wouldn't have had such an optimistic outlook. But with the establishment of the current NTD unit director, and he has all this vision around bringing in new partnerships and changing the way things are done. So, it's because of him inviting me to this event in June at Geneva, where I stood up and gave what people have described as impassioned speech about climate change, that then led to all these other invitations that then led to me going to COP, it’s led to these white papers. It's led to this connection with Parliament. It just shows that you can never be sure, and things can change."