Treading on thin ice: How studying glaciers can change the climate narrative

Written by Jelaine Gan and Sheena Davis

30 July 2024

In a wrap

- The world’s glaciers are melting faster than they can reform because of global warming, contributing to sea level rise and more frequent extreme weather events.

- Bethan Davies studies how glaciers are changing in the past, the present, and the future

- Glaciers are nature’s reservoir of fresh water, and we can still save most of them if we act now

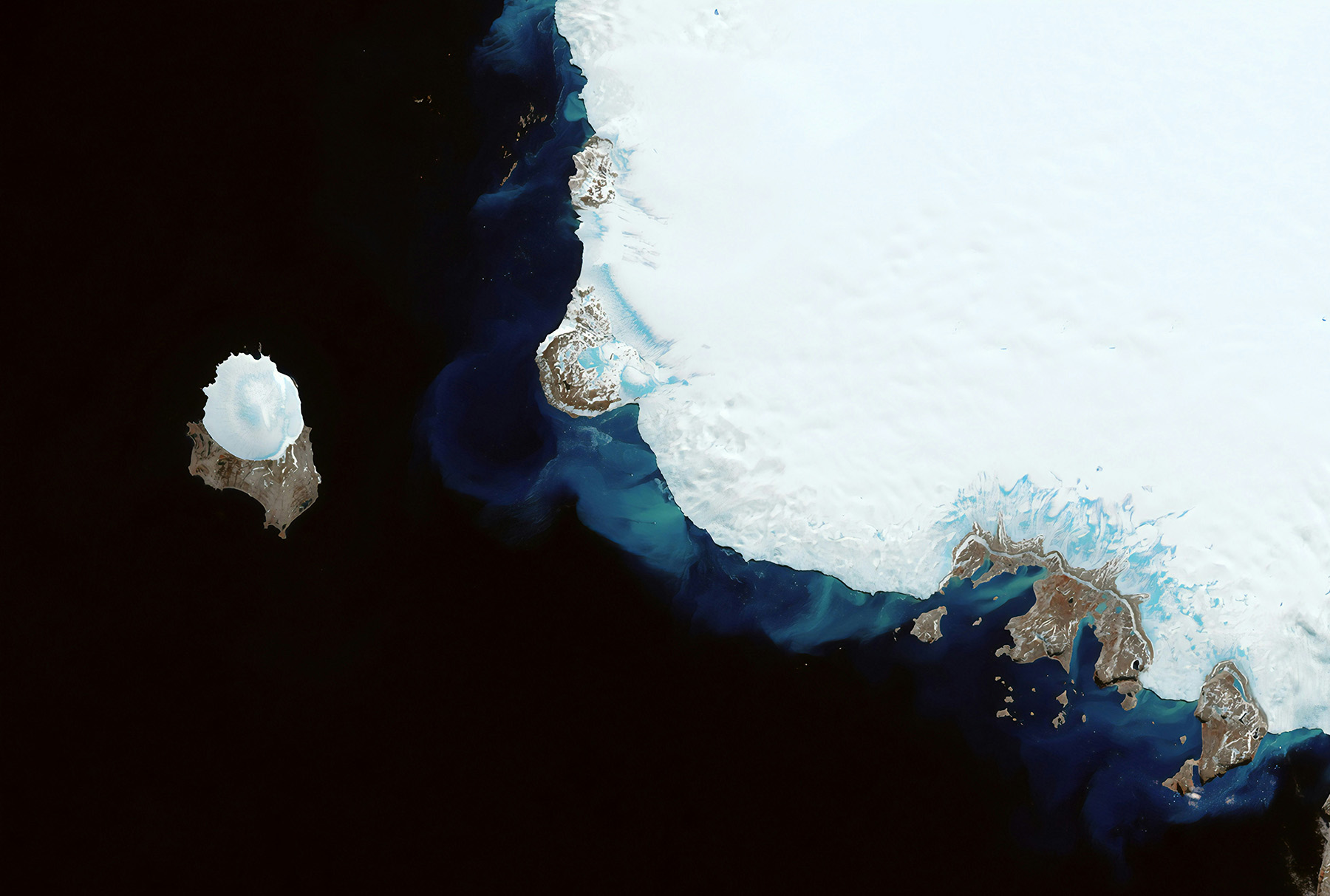

Polar bears on melting and breaking icebergs and glaciers – often the poster child of climate change. Like ice cream on a hot summer day, it is easy to imagine how global warming due to carbon emissions is melting the world’s ice. In fact, they are shrinking faster now than at any point in the last 10,000 years. But it’s not all gloom and doom; there’s more to know and understand about ice and its role in climate change. We chatted with Prof. Bethan Davies from the Department of Geography about her icebreaking (pun intended) research.

Professor Bethan Davies

Bethan is a glaciologist, or someone who studies glaciers. After doing an undergraduate degree in Geography, she became fascinated with geology during the Quaternary, a period about 2.5 M years ago that is characterized by glacial-interglacial cycles, and this was evident in the presence of rock collections stored around her office. Shifting her focus from rocks to ice, she is now a prominent Professor of Glaciology, studying how glaciers are changing today, how they've changed in the past, and how they might change in the future with the impacts of climate change.

Simple terms explained

- Glaciers: A mass of ice formed on land that constantly ‘flows’ downhill

- Ice sheet: A large mass of ice greater than 50,000 km2. Today there are only two: the Greenland Ice Sheet and the Antarctic Ice Sheet.

- Iceberg: A chunk of glacier ice that broke off and floated away into the sea or a lake.

Glaciers are vital sources of drinking water

One of Bethan’s current projects is called ‘Deplete & Retreat: the future of the Andean Water Towers’, and focuses on the glaciers, climate and hydrology of the Andes in South America. The team is with over 60 people, including local communities and researchers from Chile, Peru, Bolivia, Europe and the USA. This project aims to improve our understanding of glacier dynamics in the Andes, and in turn provide much more detailed predictions of how water availability will change in the region. As Bethan put it, "we can think of the world's mountains as water towers because they make it rain… Very moist winds from the Pacific Ocean are forced up the mountains and as they're forced up, the air cools because it's colder, and that makes it rain. That water is then stored in the snow and the glaciers, which then is released slowly." Thousands of people up and down the Andes rely on this vital source of water. It also acts a buffer against droughts.

Just a few weeks ago, Bethan was assembling a weather station in Peru. This is one of many stations that will be set-up to collect weather data such as rainfall, temperature, wind speed, etc. This observational data, coupled with satellite and aerial imagery, will be used to inform numerical simulation models on hydrology in the region. It can give us an idea of how fast the glaciers are melting and forming, under different scenarios with regards to climate change. Unfortunately, glaciers tend to melt faster than they can form or grow, and the models can tell us how much time we got left to save them.

Why should we in the UK care about ice?

The UK is an island nation surrounded by sea. Global sea level is rising at over 3 millimetres per year due to climate change, and this is due to the thermal expansion of seawater and partly contributed to by glaciers melting. This 3-millimetre increase sounds very insignificant, especially with the constant and daily changes in the tides. However, something most of us don’t really think about is that rising sea levels worsen the impact of storms. Stronger and more devastating storms will become more common, and they can result in more frequent instances of coastal flooding and even potentially cause power outages to both coastal and non-coastal communities. As Bethan pointed out, we in Newcastle are situated on the coast, and our nuclear power stations are near the coast, so we are all vulnerable.

Moreover, there are numerous societal impacts of climate change that need to be considered. Many communities across the globe, such as vulnerable island nations in the Pacific, will be affected and may be forced to migrate to safer, less affected countries, thus becoming climate change refugees. The UK will have to think about its response to this issue of climate-induced migration, which remains poorly understood.

There is hope!

Despite the ‘world of ice’ melting around her, Bethan remains positive about the future. She shared messages of hope from simulations that she has done, “The carbon that we have emitted to date does not commit us to losing all the world's glaciers and ice caps. We are very much in a place where we can change the future. If we reduce our carbon now, then we will actually retain the majority of the world's ice.” Global agreements (i.e., Paris Agreement) set a target of limiting global warming up to 1.5°C, however, she emphasized that this is not an all-or-nothing game, and that every 10th of a degree centigrade in our target limit counts.

Anyone can be a glaciologist

The field of glaciology is usually stereotyped as dangerous and physically tough. These stereotypes lead us to picture athletic, brawny researchers trudging across snow-covered terrain to carry out their fieldwork. Bethan is trying to break this image, sharing that one doesn’t have to be the strongest and fittest person to be a glaciologist. In fact, some do not leave the comfort of their homes and focus on solely satellite data and computer models. There are also various aspects to the study of glaciers which require expertise from a range of disciplines. One can be a mathematician, a geologist, or a physicist, and yet they can all be glaciologists too.

There is also the misconception that glaciology is largely a male-dominated discipline. Interestingly, in actual fact, the ratio of females to males in the field seems fairly even, especially for early career researchers. However, Bethan said, “What I haven't seen is equal numbers of women and men progress... Women professors make up a very small proportion of the senior positions in glaciology.” Based on a cursory search online, Bethan noted about five female professors in glaciology in the UK, compared to over 40 male professors.

Thoughts on the future

Talking to Bethan about the future of her field, she shared her insights about novel technologies and key messages about the climate crisis:

"I think our ability to predict different future stories under different climate summaries will improve. Large scale, ‘big data’ global analysis will become more common and more important, using AI, machine learning, and supervised classifications of data sets."

I don't think frightening people is the way forward in climate change communication. I think it's important to tell people that every small action makes a difference. In fact, the biggest and most meaningful single action a person can do is to vote right. And that's because if you vote, you put political pressure on the government, and they will take action. Writing to your MP to tell them to do something about climate change is very effective.

My positive note would be that we're at a crossroads. Every 10th of a degree matters. We can make a difference. We can change things. The easiest way to do that, and the most effective way is to vote and to write to your MP until they get the message."