Conversation Malcolm Young

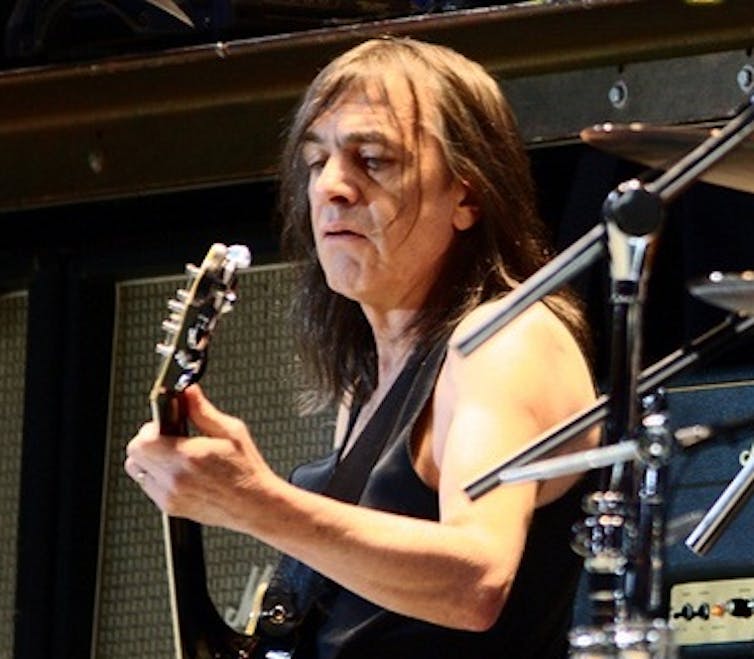

Comment: Malcolm Young helped define heavy rock’s guitar sound

Published on: 20 November 2017

Writing for The Conversation, Dr Adam Behr pays tribute to Malcom Young, the AC/DC guitarist who embodied some contradictory elements that came to be one of the defining sounds of rock.

“Unassuming” is perhaps a curious description of someone who played countless stadium shows – noted for their larger than life props – and was a driving force behind an act that sold more than 200m records. But Malcolm Young co-founder and rhythm guitarist of AC/DC embodied some contradictory elements that came to be one of the defining sounds of rock, as AC/DC also came to exemplify how a rock band works as a combined social and musical unit.

The older of the two brothers who founded the band in 1973, Malcolm wasn’t the natural centre of the band in terms of visual iconography. That rested with lead singers – Bon Scott and, latterly, Brian Johnston – and lead guitarist, his younger brother, Angus. Angus’s distinctive school uniform and stagecraft – spinning on his back, running across the stage and a “duck walk” – aligned with the band’s instantly recognisable logo and visual props like giant bells and canons. Malcolm, stolidly immobile, was a lynchpin rather than a focal point in terms of AC/DC’s branding.

But the sound was another matter. Here, Malcolm came more than anyone (with the possible exception of Keith Richards) to define rock rhythm guitar – and, by extension, the sound of heavy rock itself. His playing characterised the band’s style: taut, unshowy riffs that lodged indelibly in the listener’s memory as a consequence of their simplicity. Young’s metronomic right hand was the foundation for the pyrotechnics elsewhere.

But central to how he made this work was his understanding of space in the music. AC/DC’s association with scale and volume belies the economy in their riffs, the impact deriving from stripping back the music to its core components, allowing each chord its own space in the musical framework rather than crashing into one another. It’s telling on this front that, despite their market position as pre-eminent in heavy rock, Malcolm Young insisted that AC/DC was a “rock and roll” band. His emphasis on “swing” in the music – the roll as well as the rock – was what differentiated AC/DC from their peers, and imitators.

Family business

Sociologists differentiate between groups that are oriented around communal ideals and those orientated around work or projects. Here too, AC/DC typified the connection between social relationships and musical creativity in rock. It was very much a family business.

Few bands have managed the replacement of a key member has successfully as AC/DC, whose career-defining album Back In Black came in the wake of the death of lead singer Bon Scott in 1980 and his replacement with Brian Johnston. It was the core of the Young brothers that allowed for this, Angus providing the visual and musical centrepiece of the band, while Malcolm took care of the foundations.

Their family roots in rock and roll went back to childhood. Angus and Malcolm’s older brother George – who predeceased Malcolm by four weeks – had hits in the 1960s with The Easybeats and eventually produced many of AC/DC’s key albums.

Their nephew Stevie – son of their oldest brother, although quite close to the band members in age – also stood in for Malcolm – briefly in the late 1980s when he took a break from touring to address his alcohol dependency and, latterly, when his dementia ultimately forced him from the stage.

Malcolm Young’s own personal travails here were a model for AC/DC too. In many ways he was a guitarist – and led a band – that was avowedly backward looking. He was suspicious of new technology, preferring analogue recordings, and he avoided overt musical experimentation. Lacking an exploratory edge, he replaced this with sheer determination. The uncompromising nature of their music was echoed in Young’s own insistence on completing a world tour in 2008 despite the onset of dementia.

Looking at the waves of audience movement on the group’s live DVD from River Plate, it’s hard to believe that the motor of that wave generator had to relearn his own songs prior to each gig.

Keep it simple – not stupid

Young, and the band he founded, represented a kind of deceptive musical simplicity. But it’s easy to mistake “simple” for “stupid”. Here Malcolm Young was both the embodiment of, and a rebuke to, a series of musical clichés: the dumb rocker who leaned on a few chords, the limited rhythm player who takes a back seat to the technical ability of the lead guitarist, and the rock dinosaur who can’t operate beyond a set formula.

His refusal to stray beyond particular parameters with AC/DC’s music, though, hid the extent to which that core sound had been honed, mined from the multiple other possibilities rather than stumbled upon. His decision to focus on the development of monolithic riffs revealed an understanding that a successful band operates as more than the sum of its parts – his rhythm playing allowing the space for the eye-catching antics elsewhere, while locking down the audiences ears and bodies.

Malcolm Young, through AC/DC, perfected an approach and sound that was at once completely generic and totally individual, exerting a massive influence, even as it has proved impossible to properly replicate. For this, we salute him.

Adam Behr, Lecturer in Popular and Contemporary Music, Newcastle University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.