Conversation Voter ID

Comment: Voter ID election pilot

Published on: 1 August 2018

Dr Alistair Clark and Dr Toby S James discuss how the largest ever survey on electoral integrity at UK polling stations suggest local election pilot was unnecessary and ineffective.

The 2018 local elections in England were surrounded by a fierce debate over a pilot requiring voters to present ID at polling stations. The government had argued that a clampdown on security was needed, because it was concerned about ongoing electoral fraud in polling stations.

It’s important to have neutral evidence to judge these claims. We think our findings from the largest ever survey on electoral integrity at UK polling stations can help to achieve this.

Following up on a 2015 survey, we conducted a survey of the staff managing polling stations across England, issuing ballot papers and sealing up ballot boxes at the 2018 local elections. We asked if they had suspicions that electoral fraud was taking place and whether party agents were acting within electoral law. We also asked if voters were turned away. The survey was circulated in 42 local authorities that were not piloting voter ID and there were 2,274 responses.

Meanwhile, the Electoral Commission was evaluating the pilots, posing identical questions in the five local authorities asking voters for ID.

We are currently working on the analysis of the data and a full write up will be made publicly available on the website www.electoralmanagement.com (or on request). However, we are able to provide some early and important findings.

Voter fraud? What voter fraud?

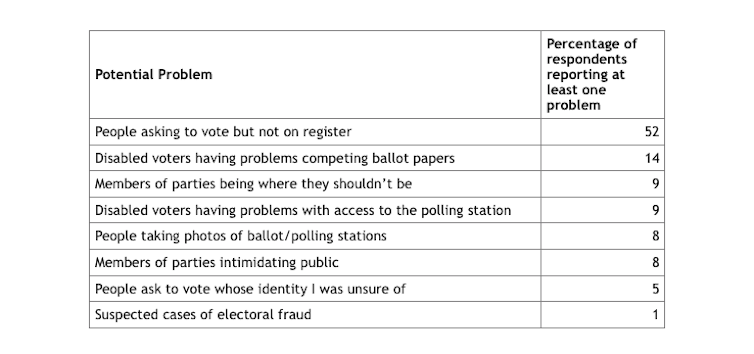

Drawing just from our own data, Table 1 reports the percentage of respondents who encountered at least one instance of a problem that is commonly thought to occur on polling day. Suspected cases of electoral fraud – the problem that voter identification is designed to eradicate – are exceptionally rare. Nearly all (99%) of respondents didn’t suspect that fraud had taken place in their polling station. Those that did, often implied that it might have been through administrative error rather than deliberate manipulation.

Instead, the most widespread problem was voters being turned away from polling stations because their name was not on the electoral register. Over half (52%) turned away at least one voter. The reasons for this included a citizen going to the wrong polling station, perhaps because changes to polling boundaries had taken place and they hadn’t checked their polling card. In some cases, it might have been because they think they can just go to the one nearest their home or the train station. These will be familiar stories for experienced electoral officials, but we now have an overall picture of the problem.

There are other areas of concern. These should also feature much higher up the government’s agenda than the problem voter ID was deigned to fix. The way people behave at polling stations was more of a problem – although even this is still uncommon. Respondents pointed to how ballot secrecy could be compromised by voters talking over voting booths. As one respondent reported, there were “men telling women who were standing in polling booths how to vote, and in loud voices”. Equally, in a few instances there were problems with, as one respondent put it, “Parking outside, with groups of supporters gathering … police had to be called”.

Most disabled voters didn’t seem to have a problem voting but 14% of poll workers did encounter a disabled voter having a problem completing their ballot paper. The suitability of polling stations was sometimes questioned.

The Electoral Commission and the government have deemed the pilots to be a success on the basis that it tightened up a security loophole. Indeed, most poll workers, responding to the Electoral Commission survey, stated that it improved security. However, it is notable that the percentage of poll workers who had suspected cases of electoral fraud in the areas that piloted voter ID, was exactly the same as those that did not. In both cases, it was just 1%. Further analysis will follow, but voter ID requirements simply don’t seem to be reducing cases of electoral fraud, presumably because they are so few and far between.

We think that regular surveys of poll workers will help to bring more evidence to the debates that surround electoral policy in the UK. As it stands, there doesn’t seem to be any evidence of electoral fraud in polling stations to warrant this being the main focus of government policy.

The Electoral Reform Society and opposition parties in parliament have claimed that the introduction of voter identification would disenfranchise voters. In recent weeks, we have seen renewed debate with an open letter of 20 charities calling for compulsory ID checks to be halted because vulnerable people would be affected. Cross-national evidence shows that voter ID requirements can reduce voter turnout. This is not just an unnecessary diversion of resources, but something that can be harmful.

The greater proportion of problems are with the convenience of registering and voting. The electoral process therefore needs to be modernised to fix this. That might involve voters being allowed to cast at any polling station with electronic poll books and automatic registration. Likewise, measures to increase accessibility and address behavioural issues in and around polling stations. The government should therefore halt the implementation of voter ID, and press ahead in the areas where there is evidence of a problem.

Toby S James, Senior Lecturer in British & Comparative Politics, University of East Anglia and Alistair Clark, Senior Lecturer in Politics, Newcastle University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.