The Conversation Music #Metoo

Comment: Why music hasn't had its defining #Metoo moment yet

Published on: 9 August 2018

Writing for The Conversation, Dr Adam Behr looks at why the music industry hasn't had a Weinstein or Cosby style watershed.

It’s now ten months since the #MeToo wave broke over Hollywood, with Harvey Weinstein at its centre. Similar revelations have shaken comedy – with Bill Cosby the most notable example – and sexism in the political realm has also been in the spotlight, ending the cabinet career of Sir Michael Fallon amid wider concerns about a culture of harrassment and abuse in Westminster.

With R&B star R Kelly’s recent release of the defiant 19-minute song I Admit in response to numerous allegations against him, questions are being asked about why the music industries have not yet faced a watershed moment comparable to Weinstein or Cosby’s downfall.

There have been some moves to highlight harassment in music, with demonstrations of solidarity at both the BRIT and Grammy awards. But there has yet to be a focal, Weinstein-style watershed moment in the music business. The reason for this is not straightforward. First of all, it’s something of a misnomer to describe the “music industry” as a monolithic whole, as opposed to distinct – if related – activities: publishing, tours, recordings and so forth. And while there are different segments of the film industry, a movie is a unified product in the way that a song, an album and a gig aren’t.

So legends and heroes have evolved in music differently to cinema. Alongside the power imbalance that also pervades Hollywood, there’s the additional issue of errant behaviour being baked into the rebel credentials of “rock'n'roll” and the closer relationship between fans and stars in music than in cinema. It’s hard to disentangle hell-raising stories of life on the road from the array of questionable acts under the spotlight of #MeToo.

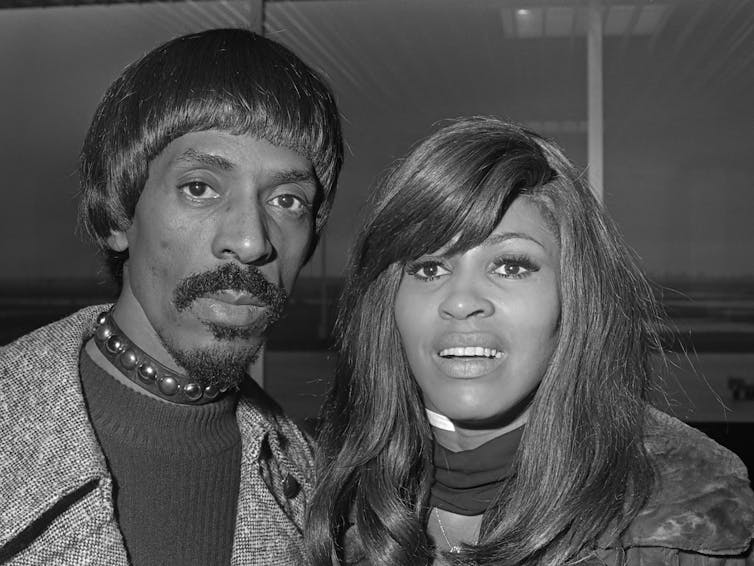

Separating the art from the artist might sometimes be necessary when the cult of the “musical genius” is tied up with instances of problematic conduct. Hugely iconic stars such as Chuck Berry, James Brown and John Lennon are on record as having committed offences from voyeurism to domestic abuse.

Numerous others are alleged to have slept with underage girls – illegal whatever “consent” was implied, even in the heyday of the rock era.

It’s also harder to “blacklist” artists, who can keep producing music and streaming directly to fans. So when, for instance, Spotify moved to pull XXXTentacion and R Kelly from playlists, it ended up rowing back on the decision on the grounds that it would have been impossible to properly police.

Change from the ground up

Fixing all of this will be difficult to achieve quickly. The possibility of powerful female artists taking a stand (as Taylor Swift did in her court victory over the DJ who had groped her in 2003) provides one point of focus. But it’s not just a matter of policing the behaviour of prominent individuals – systemic, back-of-house, changes are needed.

The UK Live Music Census showed a broad gender imbalance across different categories of musician, becoming more pronounced in the professional realm. 68% of respondents to a survey of musicians identifying as professional, 81% as semi-professional, were male. This echoes an analysis by The Guardian in October 2017 which calculated that of the 370 gigs listed for one night in October on the Ents24 listings website, 69% of the acts were made up entirely of men, while just 9% were female-only – and half of these were solo artists.

Similarly, UK Music’s Diversity survey showed women making up 60% of intern positions but only 30% of senior executive roles. Overall, women aged between 25 and 34 make up 54% of the UK music business, but they tend to leave the industry in greater numbers than male colleagues and women aged between 45 and 64 represent just 33% of the workforce.

But work is underway to develop strategies to combat sexism and harrassment in the industry. The Musicians’ Union and Incorporated Society of Musicians recently launched a joint code of practice to tackle harassment and bullying, with UK Music helping to promote their “safe space” email account for reporting harrassment, anonymously if necessary.

Problems among audience members are also moving up the agenda – organisations such as Safe Gigs for Women have identified actions for venues and festivals to reduce assault and associated predatory behaviour. Likewise, the Music Venue Trust and Music Planet Live’s initiative to bring more young women into gig promotion is aimed at fostering change at the grassroots.

If the #MeToo movement has driven change in the music industries, it’s less about claiming a high-profile scalp such as Weinstein than (hopefully) encouraging research into the scale of the problem and developing ways to address it from the ground up. This takes longer than a media storm – a storm that is all too often followed by business as usual – and it is more of an ongoing challenge. But lasting change requires thorough work over the long term – not just hashtags and speeches.

Adam Behr, Lecturer in Popular and Contemporary Music, Newcastle University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.