Conversation fracking earthquakes

Comment:Fracking causes earthquakes by design: can regulation keep up?

Published on: 12 November 2018

Writing for The Conversation, Professor Richard Davies highlights the necessary steps to make fracking-induced earthquake monitoring more effective.

Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, for shale gas has been a major concern for people in the UK since the first site to open, at Preese Hall, Lancashire, caused two earthquakes in 2011 that were strong enough for humans to feel. With local magnitudes (ML) of 2.3 and 1.5, these earthquakes were subsequently linked to the reactivation of a previously unknown natural geological fault.

Fracking was temporarily banned but after a seven-year hiatus it resumed in October 2018 at a new site at Preston New Road in Lancashire. Three days later the British Geological Survey began to detect earthquakes related to the site on their local seismic network.

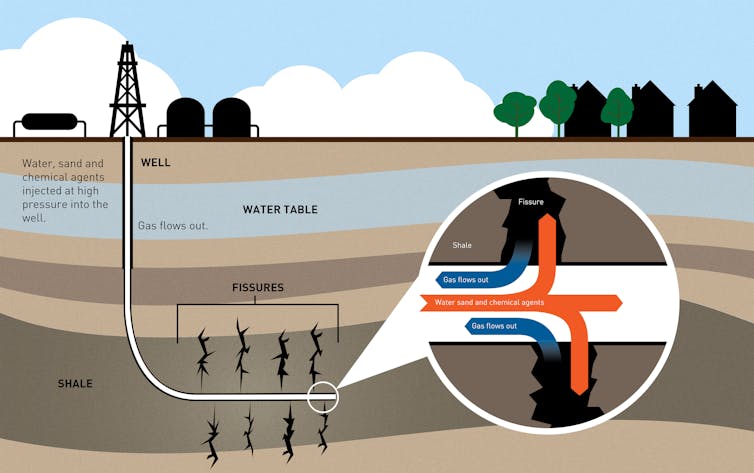

Fracking works by fracturing underground shale rock, which creates pathways along which trapped gas in the shale can be extracted. Because earthquakes occur when rock breaks, fracking is, by design, intended to bring about the very process which results in earthquakes. However, the depth of fracking operations, about 2km underground at the Preston New Road site, mean that they are too small to be felt by humans.

On the other hand, larger earthquakes with magnitudes of ML 0.5 or greater probably indicate that natural pre-existing geological faults have been reactivated, releasing stress already stored in the shale. The result can be earthquakes large enough to be felt by humans.

To reduce the likelihood of these felt earthquakes, the UK uses a regulatory traffic light system, which requires injection to be temporarily suspended if an earthquake with ML 0.5 or larger occurs. So far, six of the 36 earthquakes induced at Preston New Road have triggered this system, with operations resuming after an 18-hour monitoring period and well integrity check. The well has now produced its first natural gas.

Only the largest earthquake in the sequence, an ML 1.1 event on October 29, was felt by people, but it cannot be ruled out that more will occur during the operation.

Tough questions ahead

The shale formations that are currently targeted by fracking in England are highly (naturally) faulted, and induced earthquakes used to be relatively common as a result of coal mining. The new challenge, however, is working out how stressed these faults are and how common human-felt earthquakes might be. Good seismic monitoring of initial fracking operations will provide important data to help answer this.

There also needs to be consideration given to the current traffic light system. At what magnitude above ML 0.5 should fracking sites be required to close permanently? Alternatively, should the current stop-start cycle at Preston New Road be allowed to repeat indefinitely providing the well maintains integrity and earthquakes are not damaging or causing nuisance to local residents?

Furthermore, is a traffic light system based on magnitude really suitable? Magnitude characterises the size of an earthquake but is not a measure of ground shaking, which is the effect felt by humans at the surface. An ML 0.8 earthquake on October 26 produced far less ground shaking than a lorry typically produces as it drives past. The ground shaking was also well below the regulatory limit for quarrying operations. A traffic light system based on the intensity of ground shaking may therefore be more appropriate for fracking.

At the end of the day it is those who may be affected by the earthquakes whose opinion should carry the most weight. It remains to be seen if local residents are willing to tolerate induced earthquakes in exchange for local economic benefits.

Co-operation of stakeholders (including local residents) and research by independent organisations such as the Researching Fracking (ReFINE) consortium and the British Geological Survey will be required to tackle these questions. The answers will play a key role in determining whether UK shale gas has a future – and how it may contribute to a sustainable, affordable, and secure energy future for the nation.

Miles Wilson, PhD Candidate in the Department of Earth Sciences, Durham University; Gillian Foulger, Professor of Geophysics, Durham University; Jon Gluyas, Professor of Geoenergy, Carbon Capture and Storage, Durham University, and Richard Davies, Pro-Vice Chancellor for Engagement and Internationalisation, Newcastle University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.