Conversation cleaning work mammoths

Comment: How bison, moose and caribou do the cleaning work of mammoths

Published on: 29 April 2020

Writing for The Conversation, Maarten van Hardenbroek van Ammerstol and Ambroise Baker discuss how ancient ecosystems responded to the extinction of certain species.

Ambroise Baker, Teesside University and Maarten van Hardenbroek van Ammerstol, Newcastle University

The extinction of one species can create ripples that transform an ecosystem. That’s particularly true for so-called “ecosystem engineer” species. Beavers are one example – they dam rivers, creating ponds and channels that offer refuge for spawning fish and small mammals.

Large herbivores such as elephants, horses and reindeer are engineers too – they break down shrubs and trees to create open grasslands, habitats that benefit a wealth of species.

We know that their ancestors – such as the woolly mammoth – shaped the world around them in a similar way, but what happened to those ancient ecosystems when they died out?

Our new research published in the journal Quaternary Research studied the extinction of mammoth, wild horse and saiga antelope towards the end of the last ice age in interior Alaska, analysing fossilised dung fungal spores recovered from the bottom of lakes and ancient bones recovered from buried sediments.

Read more: Curious Kids: What effect did the asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs have on plants and trees?

We wanted to know how ancient ecosystems responded to these species dying out so that it might teach us more about mass extinctions today. What we discovered could offer hope for modern ecosystems facing biodiversity loss.

How ancient ecosystems coped with extinctions

The late-Quaternary extinctions occurred towards the end of the last ice age. In North America, they saw the loss of large herbivores and carnivores, whose relatives still roam other continents as elephants, wild horses and tigers. This was a period of rapid climate change and growing pressure from humans.

Previous research showed that 69% of large mammals were lost from North America around this time. Similar losses were seen on other continents, including Australia. The diversity of mammal species shrank, but more significant was the crash in numbers of all mammals, including species that survived the extinction event.

Previous research showed that elsewhere in the Americas, the loss of ecosystem engineers like the woolly mammoth led to an explosion in plant growth, as trees and shrubs were no longer grazed and browsed so intensively. In turn, there were larger and more frequent wildfires.

But in Alaska, our results revealed that other species of wild herbivores, including bison, moose, caribou and musk ox, increased in abundance, making up for the loss of mammoths, saiga antelopes and wild horses.

This suggests that as extinctions occurred, other large herbivores were able to fill the gap, partially taking over the lost role of ecosystem engineer. This insight from 13,000 years ago could offer hope for modern conservationists. Substituting an extinct ecosystem engineer with a similar species still living today may work to revive lost ecological processes.

Reintroducing large herbivores in this way is often referred to as “rewilding”. Today’s landscapes on most continents are empty of large vertebrate animals, largely because of the late Quaternary extinctions we studied. One of the key arguments behind rewilding is that bringing some of those species back to landscapes could boost biodiversity more broadly and create more diverse, resilient ecosystems.

But without resurrecting the woolly mammoth, our research indicates it may be possible to bring back some of the ecosystem engineering benefits of extinct species by reintroducing their living relatives or substitute species, ultimately helping surviving plants and animals to thrive.

Read more: Could resurrecting mammoths help stop Arctic emissions?

Our work in Alaska shows that the consequences of engineer extinctions are not always overwhelmingly negative. Studying this rare instance when ecosystems coped better with extinctions can help us design more effective conservation measures for megaherbivores today.

A good example of creative thinking in conservation can be found in Columbia. Here, pet hippos that escaped from Pablo Escobar’s private collection have multiplied in the wild and now appear to be recreating processes that were lost thousands of years ago when native megaherbivores died out.

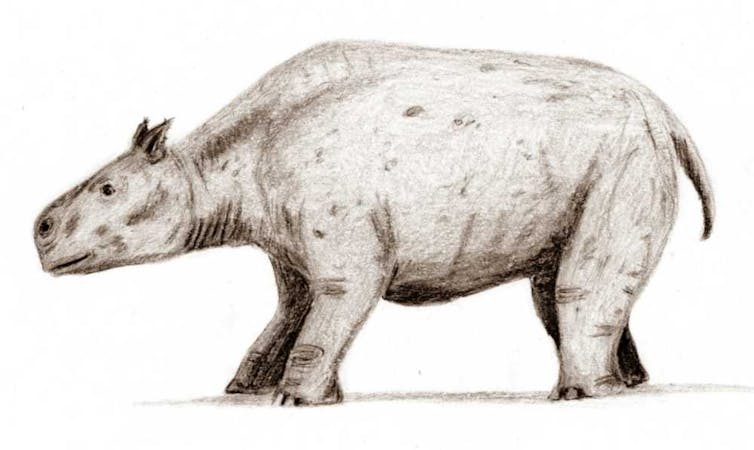

This includes the creation of well trodden hippo paths between wetlands and feeding areas on firmer ground, which help deepen water channels, disperse seeds and fertilise wetlands. Over 13,000 years ago, these processes would have been carried out by the now extinct giant llama, and semi-aquatic notoungulata.

Although it may seem an eternity since mammoths walked the Earth, our research suggests that some of the effects they had on the world around them can be resurrected without a Jurassic Park-style breakthrough in de-extinction.

Ambroise Baker, Lecturer in Biology, Teesside University and Maarten van Hardenbroek van Ammerstol, Lecturer in Physical Geography, Newcastle University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.