Conversation Glasto

Comment: Stormzy and Attenborough put spotlight on urgent concerns

Published on: 3 July 2019

Writing for The Conversation, Dr Adam Behr discusses how Glastonbury highlights the issues of the day

There’s little doubt that Glastonbury is one of the UK’s – perhaps the world’s – most iconic music festivals. It always generates headlines and while the vagaries of the British seasons often mean that many of these focus on the weather, Glastonbury’s centrality to the live music calendar means that it also acts as a faultline for broader tensions in popular music culture. In particular, it embodies the collision of popular music and politics.

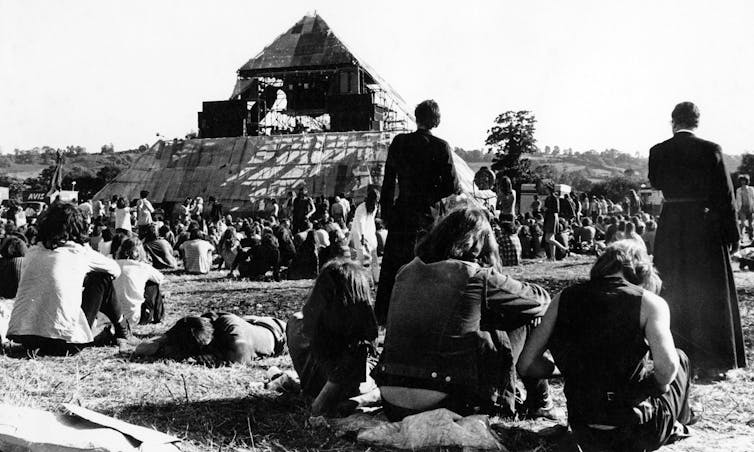

Emerging from the “free festival” movement of the 1960s, Glastonbury began in its current form in the 1970s – first as the Pilton Festival organised by Michael Eavis of Worthy Farm and then, in 1971, as the Glastonbury Fayre. That event was co-promoted with Andrew Kerr and Arabella Churchill – granddaughter of Winston – as a free “fair in the medieval tradition, embodying the legends of the area, with music, dance, poetry, theatre, lights and opportunities for spontaneous entertainments”.

After a hiatus, it reemerged under the supervision of Eavis as an impromptu stopover on the way to Stonehenge in 1978 and a charity event in 1979, after which it has run almost continually, with occasional “fallow years” to let the fields recover.

Counterculture to mainstream

Despite growing into an infrastructural behemoth attracting more than 200,000 people – even at £250 for a full weekend ticket – and broadcast live by the BBC as a mainstay of an otherwise volatile festival market, it has managed to retain a sense of countercultural appeal. If this appears somewhat contradictory, then that is partly because of longstanding paradoxes in rock and popular music culture.

With its status as an expensive site of mainstream consumption – and simultaneously an emblem of escapism from the everyday – Glastonbury’s politics are both implicit and explicit. The genre politics of popular music authenticity have been played out in debates about headline acts – remember when it was announced that rapper Jay-Z was to headline the festival in 2008. “I’m not having hip-hop at Glastonbury. It’s wrong,” complained Noel Gallagher, an objection that was largely (and wisely) ignored.

Shifting genre categories and consumption patterns in the age of streaming have diluted rock’s standing as the central sound of resistance and, by 2011, Beyoncé’s set passed without controversy.

The broader relationship of Glastonbury to British live music is debatable. On the one hand, it’s a huge showcase of talent. On the other, there’s a massive opportunity cost in terms of attention for the smaller venues and festivals that are the foundation of local music scenes.

But if it isn’t as explicitly about “youth culture” as some might assume, Glastonbury’s prominence also makes it a bellwether for broader political concerns, through both guest appearances and the surrounding political context.

Mixing the messages

In 2017, Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, riding high on a better than expected general election result, was cheered on by the signature tune of the White Stripes song Seven Nation Army recycled as a crowd chant: “Oh, Jeremy Corbyn.”

But a week is a long time in politics – never mind two years. Corbyn’s ambivalence over Brexit – and failure to recreate his triumph at the 2018 Labour Live festival – illustrate some of the practical complications of politicians mixing pop into their operations.

Indeed, qualms about Brexit were a perhaps unsurprising backdrop to the musical festivities in 2019. But Stormzy’s lambasting of would-be prime minister Boris Johnson – and his highlighting of the inequalities in the criminal justice system – showed that both the music, and the festival itself, are as politically potent as ever.

Another keynote of this year’s festival, as in the news and on the streets at large, was climate change. So the signature non-musical speaker this year was David Attenborough addressing climate change, while both the Extinction Rebellion protesters and the festival’s own attempts at more sustainable practice chimed with that theme.

This, of course, is a challenge that applies far beyond a single music festival. Another one is the problem of sexism in the music industry and Emily Eavis – who inherited the stewardship of Glastonbury from her 83-year-old father – has noted the difficulties she faces in getting some men to acknowledge that she is now in charge of booking the main stages.

A broad church

From its Leftfield speakers’ tent to the unabashed pop presence of Kylie Minogue on the main stage, Glastonbury’s sheer scope allows it to straddle the nitty-gritty of current affairs and the peaks of popular music’s ability to throw a party.

That scope also means that one of its functions is as a prism through which to view the larger political, as well as the popular cultural, picture. The oppositions between art and commerce, anti-establishment politics and mass culture, and the grassroots and mainstream have long been a feature of popular music. Glastonbury’s sometimes uneasy journey from resistant counterculture to media-friendly centrepiece of British musical culture suggests they’re unlikely to be resolved any time soon.

But the longstanding affection in which it is held, and its consequent capacity to pinpoint the urgency of matters such as climate change or inequality, suggest that perhaps they don’t need to be.

Adam Behr, Lecturer in Popular and Contemporary Music, Newcastle University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.