Conversation Nato

Comment: Ukraine War - Kremlin fears of Nato expansion

Published on: 21 September 2022

Writing for The Conversation, Professor Nick Megoran discusses how Russia’s idea of itself as endangered by Nato is crucial to understanding the war and mapping out a future path to peace.

As Russian forces withdrew in the face of the recent Ukrainian counteroffensives, the Kremlin repeated its claim that its military invaded because of the threat of Nato’s possible expansion.

This has been a constant refrain of Kremlin military briefings. For example, following the humiliating sinking of Russia’s Black Sea flagship, Moskva, in April, Margarita Simonyan, the head of broadcaster RT and a major Putin cheerleader, said:

We need to understand, when we see difficult events taking place, the losses, we are not fighting against Ukraine … from an entirely technical, military point of view we are fighting with Nato. We are fighting against an enormous armed opponent, the most powerful and in essence the only one of its kind.

It has been a recurring theme of Putin-era Russian foreign policy that an expanding Nato presents an existential threat to Russia. Western politicians and commentators generally dismiss this. They view Nato as a purely defensive alliance of voluntary members, and see Moscow’s position as a dishonest excuse for both the original invasion and subsequent battlefield setbacks.

But grasping Russia’s geopolitical idea of itself as endangered by Nato is crucial both to understanding the present war and mapping out a future path to peace.

Cold war defensive alliance

Nato was founded in 1949 with the primary aim of countering the perceived Soviet threat to the US and its European allies. The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 presented a unique opportunity to rethink security structures in Europe. With luminaries grandiloquently declaring that humanity stood upon the threshold of “the end of history” and a “borderless world”, what need was there for a cold war relic such as Nato?

Although the history of this remains a matter of some debate, present-day Russian leaders believe that the Bush administration promised that Nato would not expand if the Soviet Union permitted German reunification. George HW Bush rejected proposals for expanding the alliance, but US policy changed under former US president Bill Clinton.

Eastern European leaders requested membership and arms industry lobbyists such as the US Committee to Expand Nato campaigned vigorously for enlargement in order to open new markets for their products. Supported by influential anti-Russian hawks including Henry Kissinger and Zbigniew Brezezinski, this lobbying culminated with the 1996 passing of the NATO Enlargement Facilitation Act by both the US Senate and House of Representatives.

This occasioned a striking intervention by retired US diplomat, George Kennan, who was influential in the 1940s in formulating the US Cold War policy of “containing” Russia. In an opinion piece in the New York Times in 1997, the 92-year-old argued that “expanding Nato would be the most fateful error of American policy in the entire post-cold-war era”. It would, he cautioned, squander the “hopeful possibilities engendered by the end of the cold war,” by inflaming “nationalistic, anti-Western and militaristic tendencies” in Russia, hindering nuclear weaponry control negotiations, restoring the “atmosphere of the cold war to East-West relations,” and impelling “Russian foreign policy in directions decidedly not to our liking”.

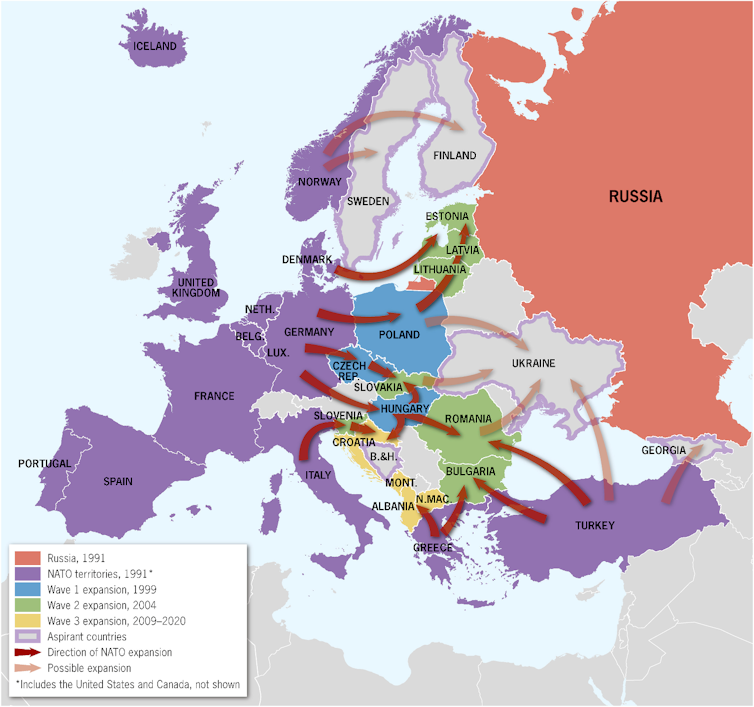

Kennan’s warning went unheeded as the Clinton, George W Bush and Obama administrations championed Nato’s eastwards creep (see map). A first wave of expansion drew in the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland in 1999. In 2004, a second wave encompassing Bulgaria, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia also opened a new Nato front with Russia by incorporating Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

A key moment was the alliance’s 2008 Bucharest Summit, which declared that “Nato welcomes Ukraine’s and Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations for membership” and “agreed today that these countries will become members of Nato”. A third wave of enlargement brought Albania, Croatia, Montenegro and North Macedonia into membership.

In 2014 Russia’s foreign minister, Sergey Lavrov, gave a landmark speech explaining the logic of Russian intervention in Ukraine. Like Kennan, he lamented that “the chance to overcome the dark legacy of the previous era, and decisively erase the dividing lines was missed”. He blamed western expansionism:

Assurances that the North Atlantic Alliance would not expand eastward – which had been given to the leadership of the Soviet Union – turned out to be empty words, for Nato’s infrastructure has continuously drawn closer to Russian borders.

But in turn, eastern European countries willingly sought Nato membership as a protection against what they perceived as their main existential threat – Russia. Russia alone is culpable for the Ukraine war and must be held fully accountable for its crimes. But this does not negate the argument that Nato expansion was a significant factor in precipitating this crisis. What matters is Russia’s perception of threat – and how badly this was misjudged by Washington, Brussels and in Kyiv.

Obstacle to peace?

In 1997 US secretary of state Madeleine Albright defended Nato expansion by predicting that:

the new Nato can do for Europe’s east what the old Nato did for Europe’s west: vanquish old hatreds, promote integration, create a secure environment for prosperity, and deter violence in the region where two world wars and the cold war began.

If this was truly the aim of Nato expansion, then it has failed spectacularly. Everything that Kennan warned of has come to pass. The current conflict increasingly looks like a Nato proxy war with Russia. That the alliance is planning to extend further into Finland and Sweden shows that it seemingly has no long-term plan for peace. Nato expansion is the very problem whose solution it purports to be.

To build a proper peace, Europe needs a sustainable security environment that transcends the divisions of military alliances and power blocs. To get there, Nato would have to understand just how threatening the map of its own enlargement looks to Russia.

Nick Megoran, Professor of Political Geography, Newcastle University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.