Heatwaves in the oceans are triggering coral bleaching on a massive scale. If greenhouse gas emissions continue unabated, such heatwaves are projected to occur at least every two years over the coming decades.

Yet, emerging research indicates that corals have at least some capacity to adapt to climate change and heat extremes. This coral heat tolerance is influenced by many different genes, each with potential variants that have arisen over vast amounts of time.

Those corals that are more heat tolerant are more likely to reproduce as the oceans warm, while those that aren’t, won’t – natural selection in action. This is how adaptive evolution can happen, even over just a few generations in relatively short periods.

To date, some have argued that the process of adaptation cannot help corals persist because the climate is changing too quickly, whereas the extreme opposite view would be that adaptation can allow corals to keep pace with climate change. We set out to determine where the answer lies with the best available science today. Can coral adaptation keep pace with ocean warming?

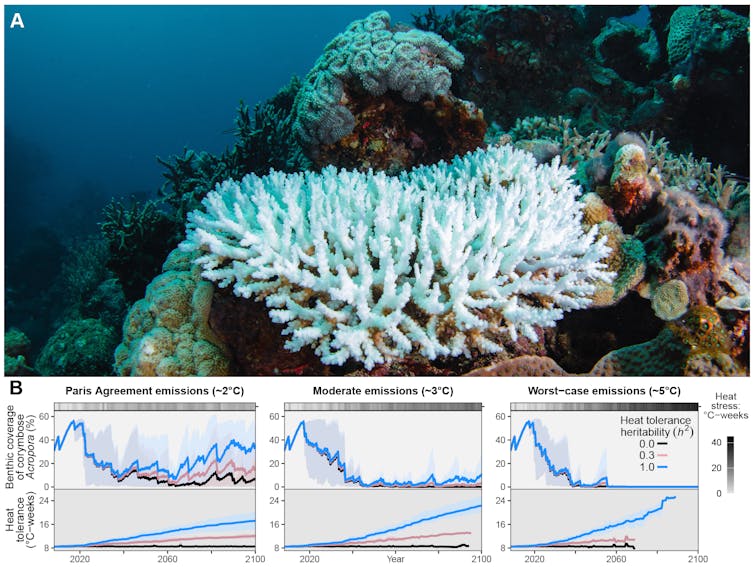

To answer this question, we developed a powerful computer program that can simulate coral reef ecosystems and how corals will evolve – in Palau, a nation of hundreds of islands in the western Pacific Ocean. This program, or model, focuses on one group of the coral genus Acropora that resembles small underwater bushes with vivid coloured branches (as shown in the photos in this article).

Acropora are a key ecological component of most coral reefs in the Pacific but, like many other coral groups, are very sensitive to changes in temperature. They can reproduce by around four years old, quicker than some other coral species. This makes them useful for scientists like us, as we may be able to see them adapt to climate change within our lifetime.

We used our model to simulate the consequences for Acropora coral under three future climate scenarios developed for the IPCC: (1) if we were to get climate change under control in the near future; (2) a more moderate scenario which we are currently headed toward; (3) if we do nothing and the world gets hotter and hotter. Relative to pre-industrial global temperatures, these climate scenarios lead to around 2°C, 3°C and 5°C of warming, respectively, by the year 2100.

Our work, published in Science, shows that adaptation via natural selection may be able to keep pace with ocean warming, but only if global warming is limited to a maximum of 2°C.

Unfortunately, we are currently more likely to experience around 3°C of warming above pre-industrial levels by the end of the century. As things stand, coral adaptation is too slow to keep up with the rate of warming.

Under a worst-case emissions scenario with warming peaking at 5°C, our model suggests a complete loss of Acropora coral populations is inevitable. This happens even if the corals were at their theoretical upper limit of adaptive potential, in which heat tolerance is entirely genetically determined, with perfect inheritance from parents to offspring (the blue lines in the graphs below).

But there is some good news: our study suggests that natural selection could offset some of the projected losses of coral reefs over the 21st century.

In the “moderate” emissions scenario that we are most likely heading towards, coral populations could only survive if they are able to adapt at least somewhat to warmer oceans (the red line in the above graph). If they’re not able to adapt at all, populations will disappear by 2070.

Even with the ability to adapt, remnant populations would be heavily depleted with an elevated risk of disappearing. But so long as populations persist, the model predicts corals will become more and more heat tolerant through natural selection, keeping open the window for evolutionary rescue beyond the 21st century.

Nevertheless, the route to coral persistence in this moderate emissions scenario is fraught with challenges. For instance, there is considerable risk of reproductive failure if populations become too depleted, with surviving individuals located too far away from one another for successful fertilisation during annual spawning events.

Where we go from here

Thanks to natural selection, there is a slim yet closing window of opportunity for Acropora and other heat-sensitive corals. This is important because it implies that the case for managing such corals is not a lost cause.

In addition to redoubling global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, we must also minimise the additional threats that affect corals, thereby giving evolution a chance to work.

There is also scope to improve upon natural adaptation rates. That’s why scientists like us are already considering innovative interventions such as “assisted evolution”. To be clear, this does not have to involve any genetic engineering – it could be achieved by identifying exceptionally tolerant corals in nature, and breeding them to spread natural heat tolerance genes more widely back on the reef.

Our research group has recently shown that selectively breeding corals for heat tolerance is a feasible option. Yet the finite scope for natural selection or even assisted evolution suggests we’ll need to do it quickly, if we are to slow the projected declines in coral.

Our work reinforces the calls to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions and improve local reef management. Together, these actions can support corals as they adapt to become more heat tolerant, helping them persist even as the oceans warm.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get our award-winning weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 40,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Liam Lachs, Postdoctoral Research Associate in Climate Change Ecology and Evolution, Newcastle University; Adriana Humanes, Postdoctoral Research Associate in Coral Reef Ecology, Newcastle University, Newcastle University; James Guest, Reader in Coral Reef Ecology, Newcastle University, and Peter J Mumby, Chair Professor, Coral Reef Ecology, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.